I recently attended a pagan gathering. It was held on private property, deep in farm country, in a secluded wood. During parts of the gathering, especially the rituals, many of those gathered, both male and female, were in various stages of undress, from wearing revealing clothing to being topless to being fully nude.

From the perspective of our Puritanical culture, this may be the most scandalous part of the gathering. My own experience with public nudity has been very limited. I’ve never been to a nude beach. And I’ve only been to a few Pagan festivals where there was nudity.

After the pagan gathering this year, I went back and read an article which I had written in 2011, after my first experience with public pagan nudity. I’m sharing it below, with only minor edits, in the hope that readers might offer criticism. It seems to me that the article still objectifies women’s bodies. There is a worrying lack of relationality in the article, I think. The women have no histories, no personhood, beyond their function for the male viewer (me). What do you think?

I’m especially interested in hearing comments from female readers.

I was a virgin festival-goer at Pagan Spirit Gathering (PSG) this year [2011]. And since I have never worked with a group that practices ritual nudity, this was my first experience with public nudity. At PSG, I encountered men and women in various stages of dress and undress, and I was surprised to discover that it was a healing experience for me.

I admit to a certain trepidation approaching this subject as a man, as I am acutely aware of how, in Western culture, the male is stereotyped as the seeing subject and the female as the seen object, and how this dynamic has contributed to the subjugation of women in myriad ways.

So I am aware that any account of a man’s visual experience of female nudity is treading dangerous ground in the (mostly) liberated culture that is Paganism.

By way of background, my own experience of female nudity over my lifetime has been ambivalent, to say the least, due largely to my Christian upbringing. I recall reading, years ago, a collection of essays entitled Men Confront Pornography, edited by Michael Kimmel. One of the contributors wrote about the centrality of men’s experience of looking, looking at women specifically, to the male psyche. He wrote about the (often unconscious) resentment that is fostered in men who are expected by our culture to look at women, are aroused by looking at women (sometimes involuntarily), but are also shamed for looking, and shamed for their arousal. I think this ambiguity in the male experience of looking at women is at the heart of misogyny.

Back when I was a Christian, the war between arousal and guilt was a defining dynamic for me. When I left Christianity, one step in healing from that unhealthy dynamic was allowing myself to look at women without internal judgment, including casual visual encounters like on the street and also pornography and erotic art.

Another step was learning a new way of looking. On this score, I was aided by a book written by tanrtic teacher, David Deida, called The Way of the Superior Man [a terrib;e title, it now seems to me] . In that book, Deida explains that physical arousal or attraction is not the result of choice, but the natural result of the flow of energy between masculine and feminine (wither hetero- or homo-sexual). Therefore, Deida writes, the desire that a woman arouses in a man (or vice versa) should be treated as a blessing, “one of nature’s gifts to you.” I was not a Pagan at the time I read this, but re-reading it now, it definitely resonates with my Pagan sensibilities.

Deida offers the following advice to men on how to develop a different visual experience of women:

“The next time you come upon a woman who sends a thrill through your body, relax into the thrill. Let her waves of feminine energy move through your body like a deep massage. Breathe fully, without resisting the joy her sighting affords you. Breathe the joy all through your body, down to your toes. Don’t stare at her … when you see her, and experience your attraction, fully allow the energy of the attraction to move freely through your body. … As you behold her, receive her vision as a blessing.”

Essentially, Deida applies the tantric practice of breathing to the experience of looking at women. Men have a tendency to hold their breath when they approach orgasm. By consciously maintaining a regular breathing pattern during intercourse, men can delay their orgasm and prolong the enjoyment of sex. Interestingly, we also unconsciously hold our breath or restrict our breathing when we look at women. I think in both instances the holding of the breath (usually accompanied by the constriction of various muscles) is a physical manifestation of an unconscious desire to control the experience. [Notice Adam’s clenched fists and rigid posture in the painting below.]

Breathing naturally when looking at an arousing woman (or man) is a way of letting go. When I breathe in, I receiving the blessing of the beauty of the woman I am looking at, but instead of holding on to it, I release it back into the world with my exhale. I compare a healthy experience of visual arousal to enjoying the beauty of a flower: seeing it, appreciating, but then leaving it, not picking the flower to take it home (thus killing it). The need to hold onto these moments of beauty and joy, to possess them, is what kills them, so to speak. In my opinion, it is what transforms [erotic] art into pornography. It is a manifestation of what Alan Watts calls “the possessive will”, the will to grasp and hold the mystery and beauty of life,

“to freeze the desired form of the living moment into an eternal and immobile possession. And so frozen, the thing is quite dead. The moment, the movement, the life has passed on and gone free.”

This simple exercise of breathing in and out transformed my visual experience of women. It transformed it from an experience dominated by an unconscious desire to possess, and is thus less likely to objectify the woman — since only objects can be possessed.

So back to my experience at PSG 2011. At the festival, I encountered three kinds of nudity. I am going to focus on the female nudity, since, as a heterosexual male, that is what has been problematic for me in my life. (I may write about male nudity in another post.) The first kind of female nudity I encountered was the completely un-self-conscious and non-erotic nudity of women at various workshops, performances, and other gatherings.

This was a healing experience for me. The women who were (partially) nude were so comfortable, and the people around them were so comfortable, that I couldn’t help be relax and be comfortable with them. It was healing because I was able to release, at least while I was there, the ironically Puritanical obsession with nude bodies that I had be taught by mainstream culture.

What was also interesting was that I began to appreciate the beauty of the nude bodies of women who, under different circumstances, I would not have found find attractive. But at the festival, everyone’s body seemed beautiful. It sounds trite, but I really experienced it that way. There was something beautiful, something divine, about sitting across from a woman in a workshop with her breasts bared, something that had nothing to do with whether she would be considered attractive in the mainstream world. She was far from the ideal female body type that mainstream culture endorses, but as I sat there, that woman “drew down” the Goddess for me; she incarnated the blessing of feminine physicality.

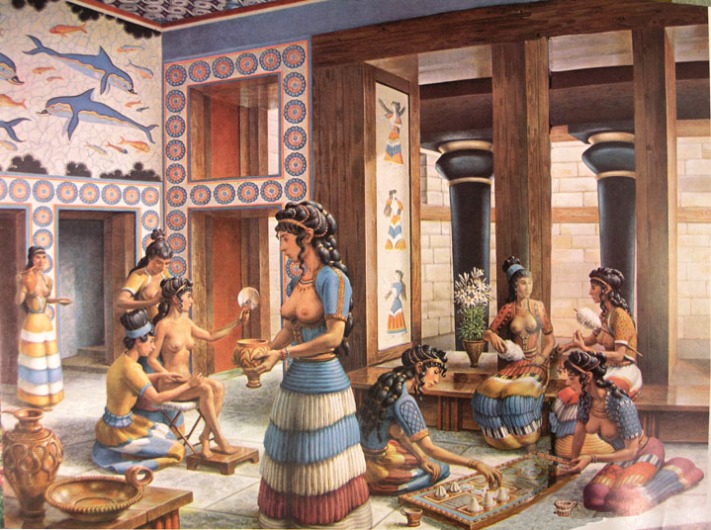

The experience called to mind a scene from the HBO series, Rome. In episode 6 of season 1, there is a brief scene with an obese woman, painted red, receiving donations in the street. She was a kind of living idol of the goddess Bona Dea. So I will call this “Bona Dea nudity”.

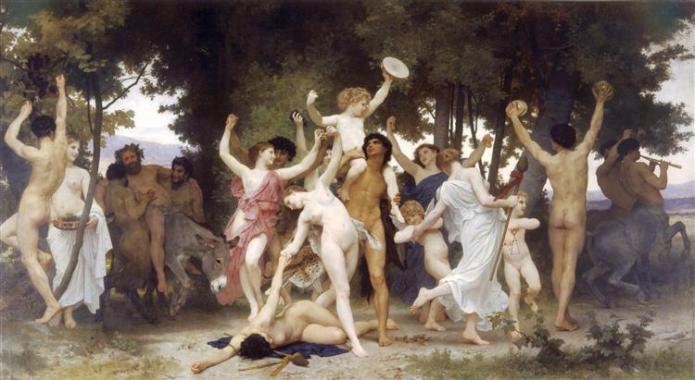

The second type of nudity I encountered was at Pan’s Ball. I have to say, I was disappointed with this event. What was supposed to be a true Bacchanalia, a sacred revel if you will, seemed like a frat party to me. There was no sacramental quality to the event a far as I could tell. And, just as at a frat party, the nudity (male and female) at the Ball seemed very self-conscious. Consequently, I felt very self-conscious.

It was like the difference between American and French films. The French films may actually show more skin, but the American films are so self-conscious about sex and nudity, you can almost hear the American film makers tittering over their own “naughtiness”. It is a product of the fact that we are attracted to and obsessed by that which we stigmatize. I was aroused by the nudity at Pan’s Ball, of course, but not comfortable. And I left early. I will call this “pseudo-bacchante nudity”.

The third type of nudity I encountered at PSG was at a drumming circle late at night near the end of the festival. A group of women danced in a circle around a low burning fire. One of them was a tall young woman with the most perfect breasts I have ever seen. Watching her dance was definitely one of the most erotic experiences of my life. But strangely, I was not uncomfortable or self-conscious.

This experience combined the un-self-consciousness of the first kind of nudity I described above (“Bona Dea nudity”), with the arousal of the second kind (“pseudo-bacchante nudity”). This was perhaps the most healing of the three experiences, because is sacramentalized not only the nude bodies of the women that I saw, but also my arousal. I will call this “true bacchante nudity”.

It was an erotic experience, but it was sacred one too. For me, it was a validation of Anne Rice’s statement that “the erotic and the wholesome are not mutually exclusive”–something that is at the heart of the Neopagan ethic, I think.

I wonder, is this experience what St. Ambrose tried ineffectually to express in the image of the “casta meretrix”, the “chaste prostitute”? Is the longing for this kind of sacred eroticism at the root of the Madonna-whore complex in our culture? Could this kind of experience help to heal men from the unhealthy ways we have learned to look at women?

Ok, so I think I was on to something here. But, looking back on it after 7 years, the article bothers me. I worry that it still objectifies women. What do you think? Leave your comments below. Comments of female readers would be especially appreciated.

P.S. Tom Swiss has written a good article about his own experience of getting naked here: The Zen Pagan: Wild Naked Pagans. I urge you to check it out too.

Yes, I think you’re right: there is certainly objectification of women here and a privileged assumption of the male gaze as entitlement.

That said, both you and the Pagan community at large are struggling with being steeped in the assumptions and prejudices of the surrounding culture. Try as we might, we can’t truly get free of our automatic equation of nudity with sexuality and sexual invitation.

I’ve been to a lot of Pagan events where there was nudity. I find it freeing and powerful, and one of the things I find powerful about it is that after a day or so, I don’t really notice it much any longer: it becomes just another way of being, not a sexual declaration.

American society in particular is deeply screwed up around the body and sex. All we can do is work to evolve our own healthier culture, and to become increasingly aware of how our orientations to them intersect with patriarchy.

Here at “the Groves of the Greene Man’s Denne,” I keep meaning to put up a sign between the side yard (parking area) and the rear areas to announce, “No Shirt, No Shoes, YOUR CHOICE!”

As to Adam’s posture and fists, I don’t know when that painting dates from, but it seems you’re possibly ascribing knowledge to the painter that he didn’t consciously even know he had.

I have noticed that often the usage in imagery of clothed males and naked females is a part of indicating who is dominant, and who is subjugated in the culture the image is part of the story of.

I’m looking forward (whether I survive that long or not) to when our species manages a change-over from the present day Dominator Culture into something of a Partnership Culture. I sometimes wonder if that change-over is a part of the Roddenberry Vision, to have taken place at some point between when he created the original Star Trek series in 1966, and the future-era the characters in the series inhabit.

I think mine is a minority opinion, but I celebrate your original article. Most of all I celebrate the baccanale nudity you were able to experience. I have always found public nudity rude or worse, as permission has not been given to stir up the various feelings men and woman experience. How does it differ from flashing? (Though obviously it becomes acceptable in certain semi-public circumstances – and I have mostly avoided those all my life). While my brain says nudity is natural, and many tribal people live near-nude, my gut feels that the potential for sacred nudity is so important, that nudity should remain a rare and mainly private thing. I actually despair at comments such as “after a day or so, I don’t really notice it much any longer: it becomes just another way of being, not a sexual declaration”. To me,that impoverishes human experience and the sacred.

The post from 2011 did seem to be somewhat about the male gaze, particularly the focus on breasts.

Maybe I should write a post about my experience as a female person who is genderqueer and bisexual in spaces with nudity.

I don’t think rarity makes it more sacred, and nor does ceasing to notice it make it unsacred. Ceasing to notice sounds like the male gaze has receded and been replaced with ease in the nude environment.

What is missing in this is that women look at men too, but it is received very differently by the mainstream culture (and I think by Pagan culture insofar as it mirrors the mainstream). If a man looks at a naked woman in a sexual way, it’s assumed to be normal. If a woman looks at a man that way, she risks being labelled a “slut” or even a vampire.

And these dynamics don’t necessarily go away when LGBT people look at other people, trans or cis, gay or straight.

As you said, the trick is not to objectify the other person — to recognize their beauty along with their humanity and personhood and sovereignty.

Hi, John,

Thanks for taking the risk to post and discuss something written so long ago in the long trajectory of decoding sexist culture. I appreciate both your candor and your self-awareness. Please don’t imagine that I’m judging you in anything that follows; from my perspective we are both on a learning journey and this is just information. Besides, I really like what you’re saying in the 2018 parts of your post.

For me, part of the objectification occurs almost at the very beginning of your 2011 piece — when you limit yourself to discussing female nudity. I recognize that your reactions to Pagan-festival male nudity would be different, especially if I assume that you’ve encountered male nudity in such group experiences as locker rooms before PSG … but by singling out female nudity and only talking about that, you’ve increased both your temptation and the temptation of the reader to speak ‘objectively’ and thus perhaps ‘objectifyingly’.

If I had written about my own first experience of Pagan-festival nudity, I might have written something very similar to this about my (cis-female identified) experience of seeing so many men nude in a context where sexual behavior was neither expected nor implied, nor sought by any party. Which was similarly liberating, though probably I felt liberated from a somewhat different set of constraints.

I agree with you about the three-or-so different kinds of group nudity experience available at PSG (we weren’t there at the same year though). I would probably also sort out my own experience in terms of time as the festival went on. One important difference between our experiences, I imagine, is that most of my life has included seeing lots and lots of male bodies naked except for genitals and buttocks — at swimming pools and lots of other summer activities — so there were no surprises about backs, shoulders, chests, bellies, thighs, etc.

At first, there were all these naked groins that I felt I ‘shouldn’t’ look at, though for different reasons than yours. My immediate first thought was ‘it might be dangerous to look’ as if the man catching me looking might interpret my look as a sexual invitation (as, alas, in so much secular American culture). Once I got used to the presence of so much dangling flesh hitherto unseen, I was very aware of our group levels of personal comfort with the situation, and it very quickly became ‘normal’ and ‘easy’ to be in such groups. At one point there was a moment of greeting in which I would normally have hugged that particular friend without reservation, and I felt in both of us a slight concern about nudity in a non-sexual hug … and then we chuckled together and embraced anyway. With no apparent discomfort on either side.

Most of the 2011 piece felt no more ‘objectifying’ to me than the paragraph I’ve just written might feel to you — and maybe we should compare notes about that. But when you characterized the one woman’s breasts as “the most perfect” you’d ever seen … how can that NOT be objectifying? That says that you

* HAVE a standard for perfect female breasts

* feel ENTITLED to evaluate our bodies against that standard

* think it appropriate to SAY you’re doing so.

And that’s objectifying.

Again, thanks for taking the risk of asking for feedback. I hope other female-identified folks will chime in and let you know how they received the piece.

Warmly,

Maggie Beaumont

I want this article to more thoroughly address how nudity feels for the nude; but you spend so much time on weighing your arousal. Arousal happens, but it is not something to dwell on. That is supposed to be one of the lessons you take away.

I agree very much with two of the points Maggie made above, in respect to the piece being limited to discussing female bodies and to the description of “perfect breasts.” That part in particular was a bit of a face-palm moment – the assumption that what makes breasts perfect is how visually arousing they are is a pretty perfect example of the male gaze in action.

Acceptance of the male gaze is also threaded into the entire premise of the essay; while the piece is personally revealing in discussing arousal and the act of looking, it reveals nothing about how you participated in the gatherings where you witnessed nudity (including whether you were nude yourself, and how that might have felt).To the women at those events, your arousal or lack thereof was most likely unimportant (well, maybe not at the bacchanal, but who knows). The post doesn’t describe any of the things that actually would have mattered to those women as people rather than objects: how you spoke to them, what kinds of social connection resulted, how you physically navigated spaces where women were nude. Readers are left to wonder if you interacted with them in any sort of personal way at all, or only as visual objects – even while you were making a good faith effort not to objectify.

I actually felt this reaction most strongly when you were talking about “Bona Dea nudity,” when arousal wasn’t part of your experience. You describe how a woman ” ‘drew down’ the Goddess for you” and “incarnated the blessing of feminine physicality.” The implication is that her nudity was “beautiful” because it served a positive emotional function for you, and that this function was divorced from her as a person and simply stemmed from her presence as a naked body.

I’m really curious if you did go on to write about male nudity as well. I think the responses you shared in this piece are a very normal phase for people to go through as we try to unpack our ingrained issues around objectification, but it also seems a lot of us stop there. We reach a sort of benign objectification, get over some of our shame around sex, and then quit there because we feel healed. But we haven’t actually dug in further to root out the underlying malady. This is similar to the lack of self-awareness that leads to “sex-positive” communities where healing is measured not by how respectfully people interact with each other, but just by how much sex everybody is having.

tl;dr: If our standard for healing is when men can objectify women in ways that feel positive and sacred, then we’re not truly moving beyond the male gaze – we’re just rehabilitating it.

Yes! This! You nailed it! Thank you